Earth Reaches Closest Point to the Sun on January 3, 2026 — What Actually Changes?

Every year in early January, a counter-intuitive cosmic milestone occurs. Earth moves to its closest point to the Sun, a position astronomers call perihelion. In 2026, that moment arrives on January 3—and it reliably triggers the same question across social media and search engines:

If Earth is closest to the Sun in January, why is it still winter in much of the world?

The answer reveals how seasons actually work—and why distance from the Sun is far less important than most people assume.

|

| Daylight Increases After Perihelion as Earth Reaches Closest Point to the Sun |

What Is Perihelion, Exactly?

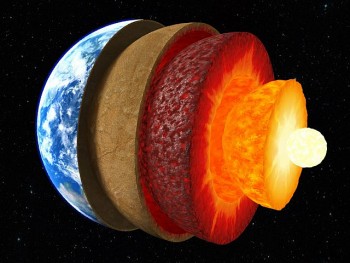

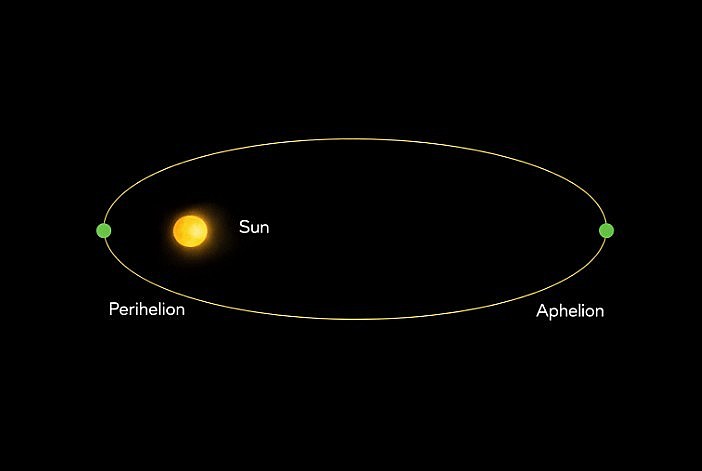

Perihelion is the point in Earth’s orbit when the planet is nearest to the Sun. Earth’s path around the Sun is not a perfect circle but a slightly elongated ellipse.

On January 3, 2026, Earth will be about 147 million kilometers (91.4 million miles) from the Sun—roughly 5 million kilometers closer than it will be in early July, when it reaches aphelion, its farthest point.

This event happens every year within a narrow date range and is one of the most predictable features of Earth’s orbit.

Does Being Closer to the Sun Make Earth Warmer?

Surprisingly, no—at least not in a way humans can feel.

The change in distance between perihelion and aphelion alters the amount of solar energy reaching Earth by only about 6–7 percent. While that difference is real and measurable, it is too small to overpower the true cause of seasons.

That cause is Earth’s axial tilt.

The Real Driver of Seasons: Earth’s Tilt

Earth is tilted about 23.5 degrees on its axis. This tilt determines how directly sunlight strikes different parts of the planet throughout the year.

In January, the Northern Hemisphere is tilted away from the Sun, meaning sunlight arrives at a lower angle. The same amount of light is spread over a larger surface area, delivering less heat. Meanwhile, the Southern Hemisphere is tilted toward the Sun, experiencing summer—even though Earth is closest to the Sun at that time.

This is why January can be bitterly cold in North America and Europe while Australia swelters under summer heat.

|

| Earth photographed by Apollo 17 on its journey to the Moon, showing the Mediterranean to Antarctica’s south polar ice cap for the first time. |

What Actually Changes at Perihelion?

Although perihelion doesn’t bring warmer weather, it does trigger several subtle but fascinating effects.

1. Earth Moves Slightly Faster

Near perihelion, Earth speeds up in its orbit due to gravitational physics. As a result, the Northern Hemisphere’s winter is slightly shorter than its summer.

2. Daylight Is Quietly Increasing

By January 3, daylight has already begun increasing following the winter solstice in late December. Sunsets start occurring later first, while sunrises remain late for a short period—creating the illusion that mornings aren’t improving yet.

3. A Psychological Turning Point

For many people, early January marks the emotional end of the darkest days. Even small increases in daylight are linked to improved mood, energy, and sleep patterns during winter.

Why Are Mornings Still So Dark in Early January?

This is one of the most confusing aspects of the season. Even as days grow longer, sunrise often continues getting later for several days.

The explanation lies in the complex interaction between Earth’s tilt, its elliptical orbit, and the way we measure time with clocks—a phenomenon astronomers refer to as the equation of time. The result is a brief mismatch between solar time and clock time.

Does Perihelion Have Anything to Do with Climate Change?

No. Perihelion is a stable and ancient feature of Earth’s orbit that has existed for billions of years. It does not explain modern global warming.

Climate change is driven by greenhouse gases trapping heat in Earth’s atmosphere, not by Earth’s small seasonal shifts in distance from the Sun. Scientists factor orbital variations into climate models to separate natural cycles from human-caused trends.

Why January 3 Still Matters

Perihelion matters not because it changes the weather, but because it challenges intuition. It reminds us that seasons are shaped by geometry, not proximity, and that the forces governing daily life are often invisible.

It also marks a quiet transition point—when daylight begins its steady return, setting the stage for longer afternoons, earlier sunrises, and eventually, spring.

FAQs

What is perihelion?

Perihelion is the point in Earth’s orbit when it is closest to the Sun, occurring in early January each year.

Why is it winter if Earth is closest to the Sun on January 3?

Because seasons are caused by Earth’s axial tilt, not distance. In January, the Northern Hemisphere tilts away from the Sun.

Does perihelion make days longer?

Not directly. Day length increases after the winter solstice, which happens before perihelion.

Is Earth closer to the Sun in winter or summer?

Closer in winter (January) and farther away in summer (July) for the Northern Hemisphere.

Does perihelion affect weather or climate?

It has minimal impact on daily weather and does not cause climate change.

Bottom line:

On January 3, 2026, Earth reaches its closest point to the Sun—but what truly shapes winter, daylight, and seasonal change isn’t distance. It’s the quiet tilt of our planet as it continues its journey through space.