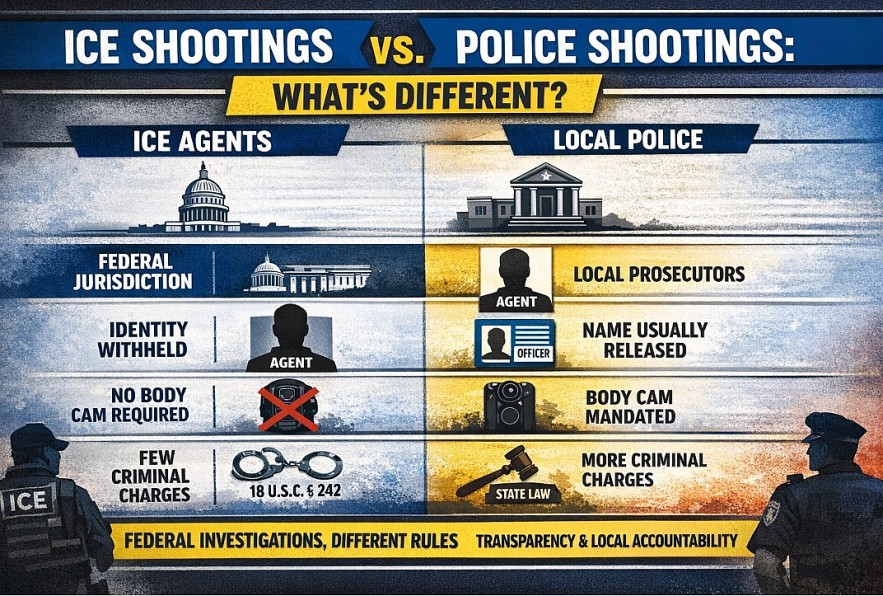

ICE Shootings vs. Police Shootings: What’s Different

The fatal shooting of Renee Nicole Good by an ICE agent in Minneapolis has revived a critical question many Americans rarely confront until tragedy strikes: Are federal agents held to the same standards as local police when they use deadly force?

The short answer is no — not in law, not in oversight, and not in accountability outcomes.

Below is a clear, statute-based breakdown, with real examples, of how ICE shootings differ from police shootings — and why that difference matters.

Read more: What Happens When an ICE Agent Fires a Fatal Shot?

|

| ICE Shootings vs. Police Shootings |

1. Different legal foundations

Local police officers operate primarily under state criminal law and are prosecuted, if at all, by county or state prosecutors.

ICE agents operate under federal authority, specifically the Department of Homeland Security. Any criminal review of an ICE shooting falls under federal civil rights law, most commonly 18 U.S.C. § 242, which makes it a crime to willfully deprive a person of constitutional rights.

That statute sets a much higher bar than state-level use-of-force laws. Prosecutors must prove not just that force was unreasonable, but that the agent knowingly and willfully violated the law.

That standard alone explains why federal agents are rarely charged.

2. Who investigates — and who does not

In police shootings, investigations often involve:

-

Internal affairs

-

State bureaus of investigation

-

Local prosecutors or special prosecutors

In ICE shootings, investigations are led by the Federal Bureau of Investigation, sometimes with state assistance.

Legally, this is permitted. Practically, it means the federal government investigates its own agents, a structure that has drawn criticism from civil rights attorneys for decades.

In the Minneapolis case, federal authorities confirmed the FBI is reviewing the shooting — not the city, not the county, and not an independent civilian body.

Read more: Renee Nicole Good Built a Life Around Writing and Poetry

3. Use-of-force rules: similar language, different context

ICE agents follow DHS use-of-force policy, which allows deadly force when an agent reasonably believes there is an imminent threat of death or serious bodily harm.

This mirrors the Supreme Court standard in Graham v. Connor (1989), which governs police use of force.

The difference lies in operational context:

-

ICE agents often work in plain clothes or tactical gear

-

Vehicles may be unmarked

-

Operations may occur without coordination with local police

Courts have repeatedly ruled that perceived threat in fast-moving vehicle encounters can justify deadly force — even when later video raises questions.

Example: In Plumhoff v. Rickard (2014), the Supreme Court ruled police were justified in firing at a fleeing vehicle, emphasizing officer perception over hindsight.

That precedent applies equally — and sometimes more deferentially — to federal agents.

4. Naming the shooter: policy, not law

There is no federal law requiring ICE to name an agent involved in a shooting.

Many police departments release officer names due to:

-

State public-records laws

-

Union contracts

-

Local political pressure

ICE faces none of those forces.

In multiple ICE shootings over the past decade — including cases in Chicago, El Paso, and now Minneapolis — the agents involved were never publicly named, even when video evidence existed.

5. Criminal charges: exceptionally rare

According to Department of Justice data, federal agents are charged under 18 U.S.C. § 242 in fewer than 1 percent of fatal use-of-force cases reviewed.

Even when charges are brought, convictions are difficult. Juries are instructed to consider:

-

The agent’s split-second judgment

-

The perceived threat at the moment force was used

That legal framework strongly favors agents.

6. Civil lawsuits: limited but meaningful

Families may file civil lawsuits under:

-

Bivens claims (constitutional violations by federal officers)

-

The Federal Tort Claims Act (FTCA)

But both paths are restricted. Qualified immunity, sovereign immunity, and limits on damages often delay or narrow cases.

Still, civil litigation is often the only avenue to force disclosure of evidence, internal policies, and agent histories.

Why Minneapolis brought this divide into focus

Public reaction to the Minneapolis shooting reflects expectations shaped by police reform movements, where transparency, body cameras, and civilian oversight are increasingly normalized.

ICE operates outside that ecosystem.

The result is a collision between local expectations and federal reality — one that leaves communities feeling powerless when a civilian dies.

The bottom line

Police shootings and ICE shootings may look similar on video. Legally, they are worlds apart.

Federal statutes, investigative structures, and accountability thresholds make ICE agents far more insulated from public scrutiny than local officers.

That difference is not accidental. It is built into the law.

And cases like Minneapolis are forcing the country to confront whether that system still deserves public trust.