Who Was the First U.S. President: George Washington or John Hanson?

For generations, Americans have learned that George Washington was the first President of the United States. His portrait hangs in classrooms. His name marks the capital. His presidency begins the official line of succession.

Yet a persistent claim resurfaces every few years: that John Hanson, not Washington, was the “real” first president.

The argument sounds convincing at first. Hanson held the title “President of the United States in Congress Assembled” beginning in 1781. Washington was not inaugurated until 1789. So who came first?

The short answer is clear: Washington was the first President of the United States as the office is defined by the Constitution. But to understand why, we need to examine the evidence carefully and compare the two offices side by side.

The Government Before Washington

• Articles of Confederation

• United States Constitution

The Articles of Confederation were ratified in 1781, during the final phase of the Revolutionary War. They created the first national framework of government for the newly independent states.

But the Articles were intentionally weak.

The framers feared centralized authority after fighting British rule. So they designed a system that:

-

Had no independent executive branch

-

Had no national judiciary

-

Gave Congress most governing authority

-

Required states to comply voluntarily with national decisions

Within this system, Congress selected a presiding officer called the “President of the United States in Congress Assembled.”

That was John Hanson’s title.

But titles alone do not define political power.

Read more: Who Was The First President of America: George Washington's Biography, Personal Life, Fun Facts

John Hanson’s Presidency: What It Was — and Wasn’t

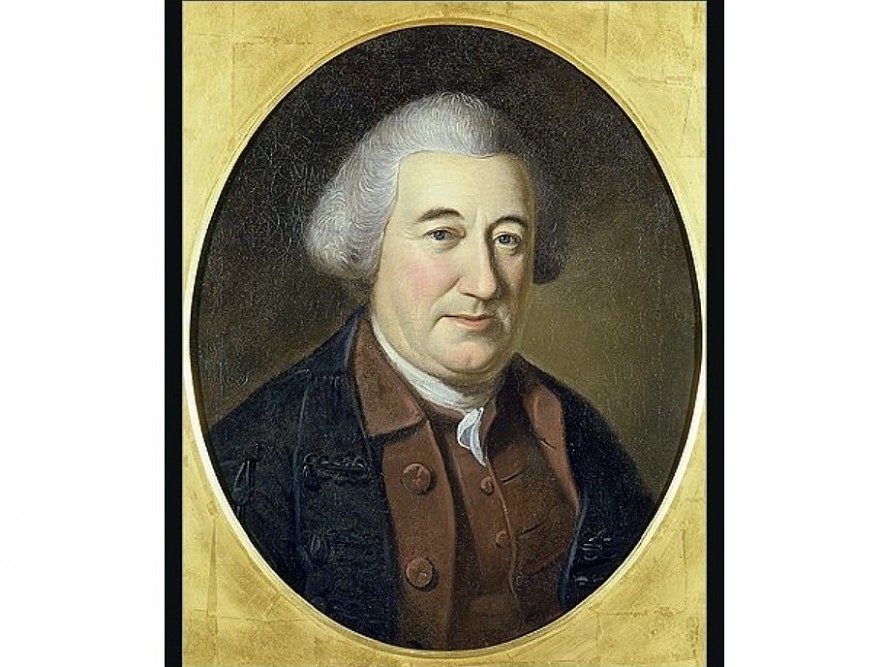

|

| Portrait of John Hanson painted by Charles Willson Peale in Philadelphia |

John Hanson served a one-year term beginning in November 1781. His responsibilities included:

-

Presiding over meetings of Congress

-

Signing official correspondence

-

Managing procedural matters

-

Overseeing certain diplomatic communications

He also played a role in chartering the Bank of North America, often described as the nation’s first central banking institution. He proclaimed a national day of thanksgiving in 1782.

These were meaningful actions. But they did not amount to executive authority in the modern sense.

Under the Articles:

-

Hanson could not enforce laws.

-

He could not command troops independently.

-

He could not veto legislation.

-

He did not appoint cabinet officials.

-

He was chosen by congressional delegates, not by electors or voters.

-

His office existed within the legislative branch.

In modern terms, his role resembled a presiding officer of a legislature rather than a chief executive.

The Confederation Congress remained the ultimate authority. The president of Congress had limited autonomy.

The Eight Confederation Presidents

Between 1781 and 1789, eight men held the title:

-

John Hanson

-

Elias Boudinot

-

Thomas Mifflin

-

Richard Henry Lee

-

John Hancock

-

Nathaniel Gorham

-

Arthur St. Clair

-

Cyrus Griffin

Their terms were brief. None exercised executive power comparable to what later presidents would wield.

Importantly, the office itself did not survive the transition to the Constitution. It was replaced.

That institutional replacement is central to the debate.

Read more: 15 Mind-Blowing Facts Most Americans Don’t Know About the USA

The Constitutional Break: A New Office Entirely

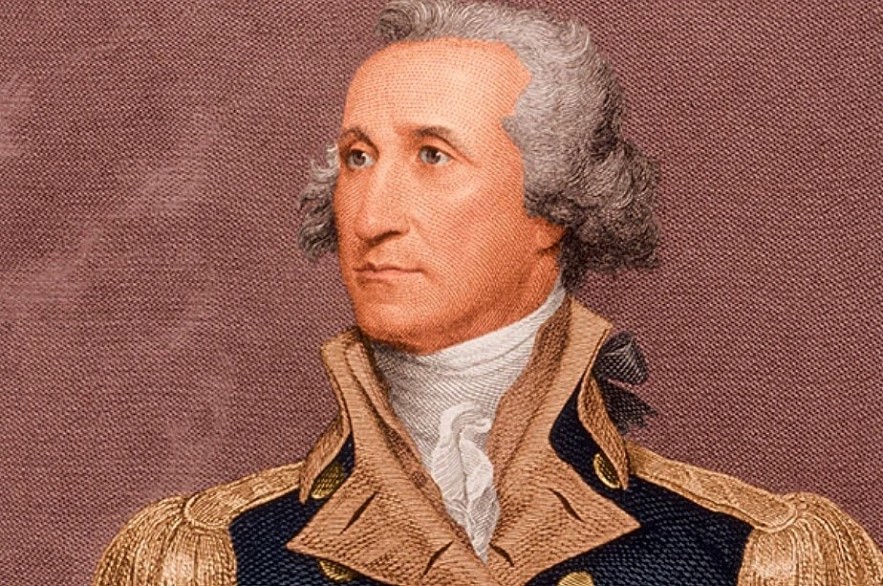

|

| George Washington |

In 1787, delegates met in Philadelphia at the Constitutional Convention. They concluded that the Articles had failed to provide sufficient national cohesion.

The Constitution created:

-

A separate executive branch

-

A President independent of Congress

-

Defined powers including veto authority

-

Command of the armed forces

-

Authority to appoint federal officers

-

Responsibility to enforce federal law

This was not an adjustment. It was a structural redesign.

When Washington was unanimously elected by presidential electors in 1789, he did not step into Hanson’s old job. He stepped into a newly created office with constitutional authority.

The presidency began as an executive branch position in 1789.

What Do Historians and Official Records Say?

The National Archives, the Library of Congress, and virtually every major academic historian recognize Washington as the first President of the United States.

The official presidential numbering maintained by the U.S. government begins with Washington as President No. 1.

Why?

Because historical continuity follows constitutional structure, not title similarity.

There is no constitutional line of succession from John Hanson to George Washington. The office under the Articles ceased to exist. A new executive office began.

Even the Constitutional Convention debates make clear that the framers were designing something unprecedented in American governance: a single executive with defined authority.

That office had no true equivalent under the Articles.

Why the John Hanson Claim Persists

The claim that Hanson was the “real first president” tends to surface for three reasons:

• The title sounds identical. “President of the United States” appears in his formal designation.

• Timing confusion. Hanson served before Washington.

• Simplified historical narratives. The transitional period between 1781 and 1789 is often overlooked in public education.

But similarity in title does not equal institutional equivalence.

If the Articles’ presiding officer had functioned as a national executive, historians would recognize that continuity. They do not.

Why Washington’s Presidency Was Foundational

Washington did more than occupy a new office. He shaped it.

He established:

-

The two-term precedent

-

The cabinet system

-

Neutrality principles in foreign affairs

-

Peaceful transfer of power

His presidency set norms that lasted for generations.

No such executive precedents were established under the Articles because the office lacked independent executive authority.

The presidency Americans recognize today begins with Washington because the institution itself began with Washington.

The Final Answer: Who Was First?

John Hanson was the first presiding officer of Congress under the Articles of Confederation after ratification.

George Washington was the first President of the United States under the Constitution.

Because the modern presidency is defined by the Constitution, Washington is universally recognized as the first U.S. president.

The two offices were not the same. The Constitution created a new branch of government, not a continuation of the old one.

FAQs

Was John Hanson ever considered President of the United States?

Yes, he held the title “President of the United States in Congress Assembled.” However, the position was legislative and ceremonial, not executive.

Did the presidency exist before 1789?

Not in its constitutional form. The executive branch was created by the Constitution and began operating in 1789.

Why does the government list Washington as President No. 1?

Because the official line of presidents follows the constitutional executive branch, not the earlier legislative presiding officers.

Did John Hanson have powers similar to modern presidents?

No. He did not have executive authority, enforcement power, or command over the armed forces.

Conclusion

The debate over whether George Washington or John Hanson was the first president reflects a misunderstanding of institutional change.

The Articles of Confederation created a weak legislative presidency. The Constitution created a strong executive presidency.

They were different offices in different governmental systems.

When Americans ask who the first president was, they are asking about the constitutional office that still exists today.

That office began in 1789.

And its first holder was George Washington.