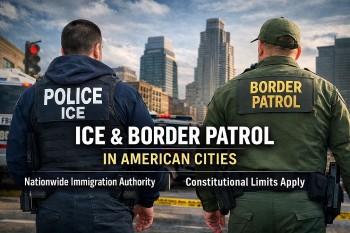

When Local Police Help ICE: The 287(g) Program and Its Legal Limits

|

| The 287(g) program |

In some parts of the United States, immigration enforcement does not stop at federal agents. Local police and sheriff’s deputies may also take part—under a program known as 287(g).

Supporters describe it as a force multiplier. Critics warn it blurs constitutional lines. Both sides agree on one thing: 287(g) changes how immigration enforcement works on the ground, and it carries serious legal consequences.

What Is the 287(g) Program?

The 287(g) program comes from Section 287(g) of the Immigration and Nationality Act (8 U.S.C. § 1357(g)). It allows the federal government to delegate certain immigration enforcement powers to state or local law enforcement agencies.

Under a formal agreement with Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), selected officers receive training and are authorized to perform limited immigration functions under ICE supervision.

Statute text (Cornell Law):

https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/8/1357

What Local Officers Can Do Under 287(g)

The exact authority depends on the agreement type, but commonly includes:

-

Interviewing people in local jails about immigration status

-

Accessing federal immigration databases

-

Issuing immigration detainers

-

Preparing charging documents for removal proceedings

Most modern agreements focus on jail-based enforcement, not street patrols.

What 287(g) Does Not Allow

Even with a 287(g) agreement, local officers do not gain unlimited power.

They may not:

-

Stop people solely to check immigration status

-

Conduct searches or arrests without Fourth Amendment justification

-

Ignore constitutional protections against racial profiling

ICE itself has acknowledged that civil immigration enforcement must still comply with the Constitution.

The Fourth Amendment Still Governs Stops and Arrests

Courts have been clear: delegation does not erase constitutional limits.

A local officer acting under 287(g) must still have:

-

Reasonable suspicion for a stop

-

Probable cause for an arrest

Race, ethnicity, accent, or appearance cannot serve as the basis for enforcement.

In Melendres v. Arpaio (D. Ariz. 2013), a federal court found that immigration enforcement practices tied to a sheriff’s office—including 287(g)-style operations—violated the Fourth Amendment and Equal Protection Clause.

https://www.aclu.org/cases/melendres-v-arpaio

Read more:

- ICE at Work: Your Rights During Workplace Raids, I-9 Audits, and Interviews

- Is Warning Others About ICE Illegal? Obstruction Laws vs First Amendment Protection

- What is the 100-Mile Border Zone, And How Far ICE and Border Patrol Powers Really Go

- ICE Agents Explained: Who They Are, What They Do, and Why They’re Under Scrutiny

- Border Patrol Agents Explained: Who They Are, What They Do, and How They Differ from ICE Agents

Liability Risks for Local Governments

One reason many jurisdictions avoid 287(g) is legal exposure.

Unlike ICE agents, local officers:

-

Are directly employed by cities or counties

-

Expose those governments to civil-rights lawsuits

Courts have held counties responsible for:

-

Unlawful detention based on ICE requests

-

Prolonged jail holds without judicial warrants

These cases can result in costly settlements and consent decrees.

How Widespread Is 287(g)?

Participation has fluctuated with presidential administrations.

As of recent years:

-

Fewer than 150 agencies nationwide participate

-

Most agreements are concentrated in the South and Southeast

-

Many large cities and states have explicitly rejected the program

ICE publishes current agreements here:

https://www.ice.gov/identify-and-arrest/287g

Community Impact and Policing Concerns

Multiple studies and police organizations have warned that immigration enforcement by local police can:

-

Reduce trust in law enforcement

-

Discourage crime reporting

-

Make witnesses less willing to cooperate

For this reason, many police chiefs argue that immigration enforcement undermines public safety policing, even when legal.

Common Myths—Clarified

Myth: 287(g) turns local police into ICE.

Reality: Authority is limited, supervised, and constitutionally constrained.

Myth: Officers can check status during traffic stops.

Reality: Only if the stop is lawful and not prolonged for immigration purposes.

Myth: Counties are required to join 287(g).

Reality: Participation is entirely voluntary.

Quick Comparison

| Issue | With 287(g) | Without 287(g) |

|---|---|---|

| Local immigration questioning | Limited | Rare |

| ICE database access | Yes | No |

| Liability risk for county | Higher | Lower |

| Federal supervision | Required | N/A |

FAQs

Can a county end a 287(g) agreement?

Yes. Agreements can be terminated by the local government or ICE.

Does 287(g) override sanctuary policies?

No. Jurisdictions choose one approach or the other.

Can officers act independently of ICE?

No. Actions must remain within delegated authority and supervision.

Does 287(g) apply on the street?

Most current agreements are jail-based, not patrol-based.

Why This Matters

The 287(g) program sits at the intersection of federal power, local discretion, and constitutional rights.

It shows how immigration enforcement can expand through cooperation—but also how easily constitutional violations and liability can follow when lines blur.

Understanding 287(g) helps explain why some communities embrace it, others reject it, and courts scrutinize it closely.